In mid-May, consumers nominated produce from the Cape Town Market in Epping. They wanted to know if the maximum residue level (MRL) for pesticides and herbicides is being adhered to for fresh produce moving through the market, as prescribed by government regulations.

In mid-May, consumers nominated produce from the Cape Town Market in Epping. They wanted to know if the maximum residue level (MRL) for pesticides and herbicides is being adhered to for fresh produce moving through the market, as prescribed by government regulations.

While this is not an explicit labelling claim, there is an implied claim that produce sold at the market complies with regulations. Cape Town Market moves 280,000 tons of fresh produce per annum and considering that most Capetonians eat fruit or vegetables that move through this platform via various shops, chain stores and restaurants, it is a particularly important investigation. TOPIC launched into its seventh investigation to verify the facts.

First contact with CT Market

In line with our policy of engagement, on 17 May we contacted the Cape Town Market to set up a meeting. A month later, we met with Joint Trading Manager, Adrian De Villiers and the Chair of the Cape Town Market Agents Association (CTMAA), Uthmaan Rhoda. We were told that the market keeps concise records of each fresh produce consignment delivered, which is linked to a specific supplier in the database. We were further informed that the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) assesses food grade and quality and has a satellite office at the Market, that MRL levels are governed by SA-GAP, Euro-Gap and Global-GAP (GAP standing for Good Agricultural Practices), and that pesticide and herbicide testing is done for DAFF via independent laboratories.

In line with our policy of engagement, on 17 May we contacted the Cape Town Market to set up a meeting. A month later, we met with Joint Trading Manager, Adrian De Villiers and the Chair of the Cape Town Market Agents Association (CTMAA), Uthmaan Rhoda. We were told that the market keeps concise records of each fresh produce consignment delivered, which is linked to a specific supplier in the database. We were further informed that the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) assesses food grade and quality and has a satellite office at the Market, that MRL levels are governed by SA-GAP, Euro-Gap and Global-GAP (GAP standing for Good Agricultural Practices), and that pesticide and herbicide testing is done for DAFF via independent laboratories.

Conversations with the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF)

At the end of June, we spoke to several DAFF representatives, including those positioned in the satellite office at the Market. All representatives informed us that it is not in DAFF’s mandate to do MRL testing on produce for the local market, as they only test for export. The mandate for MRL testing lies with Department of Health (DoH).

At the end of June, we spoke to several DAFF representatives, including those positioned in the satellite office at the Market. All representatives informed us that it is not in DAFF’s mandate to do MRL testing on produce for the local market, as they only test for export. The mandate for MRL testing lies with Department of Health (DoH).

The responsible party: Department of Health (DoH)

We were then referred to the Cape Town City Health Department who confirmed that no testing was currently taking place due to local laboratory closure. After a few weeks of asking, we received the following response from City of Cape Town on 1 September:

We were then referred to the Cape Town City Health Department who confirmed that no testing was currently taking place due to local laboratory closure. After a few weeks of asking, we received the following response from City of Cape Town on 1 September:

“The Regulations that govern the maximum limits for pesticide residue that may be present in foodstuffs fall under the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act. The analyses of products sampled for pesticide residues on fruit and vegetables used to be performed by the National Department of Health’s Forensic Chemistry Laboratory.

These were however stopped due to operational challenges and resulted in City Health no longer submitting samples for residue analyses. In consultation with the National Department of Health it was recently learned that discussions are underway with the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) to establish a Memorandum of Understanding whereby the DAFF laboratories will analyse products submitted by local authorities for residue levels on fruit and vegetables.

All fruit and vegetables destined for export are analysed by the DAFF’s inspection authority, the Perishable Product Export Control Board. Many of these producers also provide products to the local markets.

It needs to be highlighted that both the registration of all pesticides as well as the actual crop spraying programme of producers is the mandate of the DAFF and not the Department of Health or local authorities. There is usually a prescribed period between the last spray of the crops and harvesting. It should also be noted that the residual levels reduce over time.

During the years that City Health took samples at fresh produce markets and packers, very few transgressions were ever observed.

Analyses of this nature are expensive and since the Forensic Chemistry Laboratory performs the analyses of products free to local authorities, no budget provision is made for it currently.

Herbicides are not a local authority competency and solely that of the DAFF.”

In line with our rights under the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA), we asked City Health if we could access the reports where transgressions were observed when testing was still conducted. We were subsequently informed that “records are no longer available as on an annual basis the old files, records are destroyed to make way for new documents.”

Randomly selected samples for testing

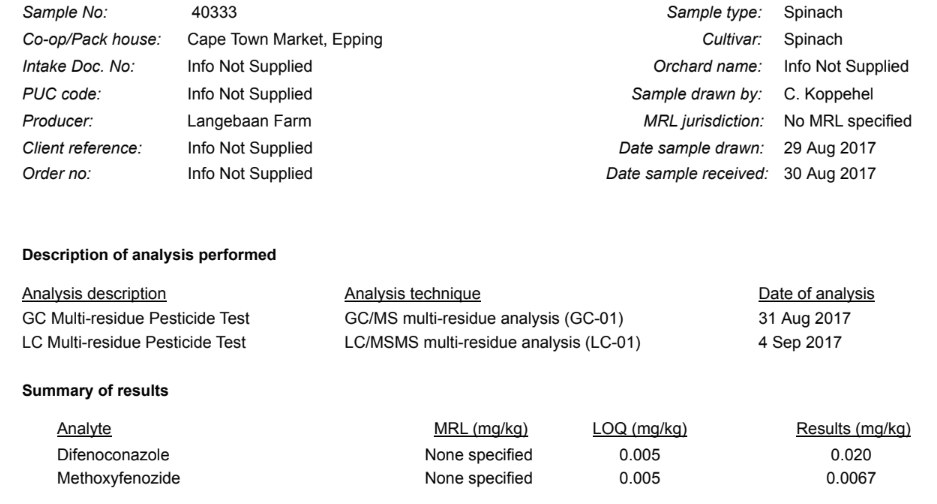

On 29 August, the TOPIC team visited Cape Town Market again and this time, randomly purchased spinach and tomatoes for testing. Produce was sent to the lab to see whether it complies with the maximum residue level for pesticides and herbicides.

The results were as follows:

Pyraclostrobin over SA MRL limit

Of all the pesticides/herbicides found in the multi-residue analysis, only pyraclostrobin is above the 2017 MRL limit set by the Department of Health (DoH) for tomatoes. The amount found was 0.027mg/kg and the local MRL is 0.01mg/kg. Although this is nearly three times the SA regulated level, it is well under the defined EU MRL level of 0.3mg/kg.

No MRL set for Difenoconazole

Although an amount of 0.02mg/kg was found of the chemical difenoconazole on the spinach, no MRL has been set by the DoH which raises the question as to whether it is registered for use in the country.

According to the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), difenoconazole is not registered for use on spinach but they stated that new registrations of agricultural crop remedies occur continuously. DAFF is working on compiling a database of registered agricultural remedies but referred us to the Association of Veterinary and Crop Associations of South Africa (AVCASA) website on which it appears that difenoconazole is registered for use in SA.

The 0.02mg/kg found of difenoconazole is also below the EU MRL value of 2.0mg/kg.

No MRL set for Methoxyfenozide

An amount of 0.0067mg/kg was found of the pesticide methoxyfenozide for which no MRL has been set by DoH. DAFF informed us that a MRL should have been set for methoxyfenozide as it is registered for use on spinach and that they are working on rectifying this matter.

Just like with pyraclostrobin and difenoconazole, the 0.0067mg/kg found of difenoconazole was also way below the EU MRL value of 4.0mg/kg.

Propargite is banned in the EU

Also of interest is the acaricide (meaning poisonous to mites or ticks) propargite which is banned in the EU. Propargite is used for control of mites on crops and the EU only allows very low residues that could be due to either persistence of the pesticide in the environment or the use of this product in third countries. Propargite is considered to be a ‘probable carcinogenic’ and is ‘very bioaccumulative’ according to a document published by UTZ.

According to research done by the European Food Safety Authority, propargite toxicity to aquatic organisms was found to be very high, the risk from secondary poisoning to birds was also identified as high, and so was the risk to mammals from consumption of contaminated water and its long-term effects. “Propargite exerts carcinogenic potential on different organs in two strains of rats and a genotoxic mode of action cannot be disregarded. No reliable reference values could be set at this stage until a new valid genotoxicity data package with the proposed specification is available. Therefore, the risk assessment could not be conducted leading to a critical area of concern.”

Responses from City Health

We circulated the results with stakeholders such as City Health and the Cape Town Market. We received the following response from Dr Helénè Visser, Manager: Specialised Health at City Health: “In general City Health can only formally deal with samples that were taken by the Environmental Health Practitioners within its area of jurisdiction. Therefore if producers are within the City boundaries the department interacts with them directly and where the producers are outside of the City, the information is usually forwarded to the relevant local authority.”

“The results are none the less still of value. The best option in this case is to interact with the Municipalities where the products were produced. You are welcome to provide us with the details and I will pass it on to the management and copy you in. This information will certainly raise awareness and producers should note the oversight from organisations such as TOPIC SA.”

TOPIC was further told that the “sampling stopped about five years ago” with no date when it will resume and that “discussions between the Department of Health and the Department of Agriculture are in progress.”

Responses from Cape Town Market

We sent the results, from Hortec, a local ISO 17025:2005 and SANAS accredited analytical company, to Cape Town Market for comment. We received a reply from Uthmaan Rhoda, the Chair of the Cape Town Market Agents Association: “Please note the following, that random sample purchases and a lab that is not specified as an accredited lab is cause for concern.” We asked several times for clarification of this concern, but as by the date of publishing had not received a substantive response.

Rhoda further commented: “As for the sampling and lab results, you have not followed up with the suppliers of the samples purchased and their spraying programmes. This would confirm your results or show up difference between your results and the spraying programmes of producers.”

We have asked repeatedly for contact details for the two suppliers of the random samples – Prospect Tomatoes and Langebaan Plaas, but Cape Town Market refers us to Cape Town Market Agents Association who have not been forthcoming.

We have asked repeatedly for contact details for the two suppliers of the random samples – Prospect Tomatoes and Langebaan Plaas, but Cape Town Market refers us to Cape Town Market Agents Association who have not been forthcoming.

The TOPIC team contacted Prospect Tomatoes directly two weeks before publishing this and emailed them the lab results for comment but they also did not reply to date.

We were not able to find any other representative of the market or related bodies who were prepared to comment on the record.

Comments from stakeholders

TOPIC asked various relevant parties for comment on the investigation.

Luke Metelerkamp from the Centre For Complex Systems In Transition, Stellenbosch University said: “Cape Town Market is a central point where many farmers bring their produce for resale on to exporters, local supermarkets, bakkie traders and other vendors. In producing this food, a wide range of synthetic chemicals are used, many of which are toxic to consumers, farm workers and the environment when not utilised correctly. In recognition of this risk, there are mechanisms in place to check toxic chemical residues on fresh produce exports but no functioning mechanism is in place to protect local consumers from the proven long-term health effects of agricultural chemicals. This is a public health risk.”

Luke Metelerkamp from the Centre For Complex Systems In Transition, Stellenbosch University said: “Cape Town Market is a central point where many farmers bring their produce for resale on to exporters, local supermarkets, bakkie traders and other vendors. In producing this food, a wide range of synthetic chemicals are used, many of which are toxic to consumers, farm workers and the environment when not utilised correctly. In recognition of this risk, there are mechanisms in place to check toxic chemical residues on fresh produce exports but no functioning mechanism is in place to protect local consumers from the proven long-term health effects of agricultural chemicals. This is a public health risk.”

“Because fresh produce markets tend to supply food to lower-cost outlets, the poor are placed at a disproportionate risk. Consumers are either unaware of the risk or incorrectly assume that there are mechanisms in place to protect them,” he continued.

“While the lack of consumer protection uncovered is alarming, the substantial difficulties in safely regulating the health risks of agricultural poisons are not unique to South Africa. This poses the need to re-evaluate the assumptions upon which potentially toxic agricultural chemicals are licensed for use in South Africa and other developing country contexts where the ability to safely regulate their usage does not exist,” Metelerkamp said.

Professor Leslie London, board member of the People’s Health Movement, had the following to say: “This is not a new problem. Testing for pesticides is an expensive business. Farmers who export have the produce tested because their livelihood (and large profits) depend on their produce getting through strict phytosanitary controls in the North. But if a farmer is producing for the local market, they more or less know that there is virtually no testing domestically. The reason is partly expense of testing and partly lack of skilled labs in SA to do the testing.

Professor Leslie London, board member of the People’s Health Movement, had the following to say: “This is not a new problem. Testing for pesticides is an expensive business. Farmers who export have the produce tested because their livelihood (and large profits) depend on their produce getting through strict phytosanitary controls in the North. But if a farmer is producing for the local market, they more or less know that there is virtually no testing domestically. The reason is partly expense of testing and partly lack of skilled labs in SA to do the testing.

“If a local authority has a limited budget, it is much more likely to use the money on identifying bacterial contamination that is likely to cause outbreaks than it is to spend on a few tests of chemical contamination. That means that what we eat is effectively unmonitored.

“Everyone has to shoulder some responsibility – government, farmers, pesticide industry – for this state of unregulated affairs. But since you don’t drop down dead of chronic pesticide consumption (unlike babies with diarrhoea, or children swallowing pesticides by accident) there is no screaming headline on this issue.”

In conclusion…

This investigation has led the TOPIC team down a rabbit hole of local and national government departments and employees. It is clear that there is a big gap in food safety where the South African consumer is not being protected and it is due to fragmentation of governmental responsibilities. This contrasts with exported produce, which is carefully tested.

The lack of response from the market, agents and source farms is also a concern.

We will continue to await responses from the market and source farms, and will post here again when there is news. We will also do further testing if funds are available to cover the laboratory costs.

4 comments